Caption

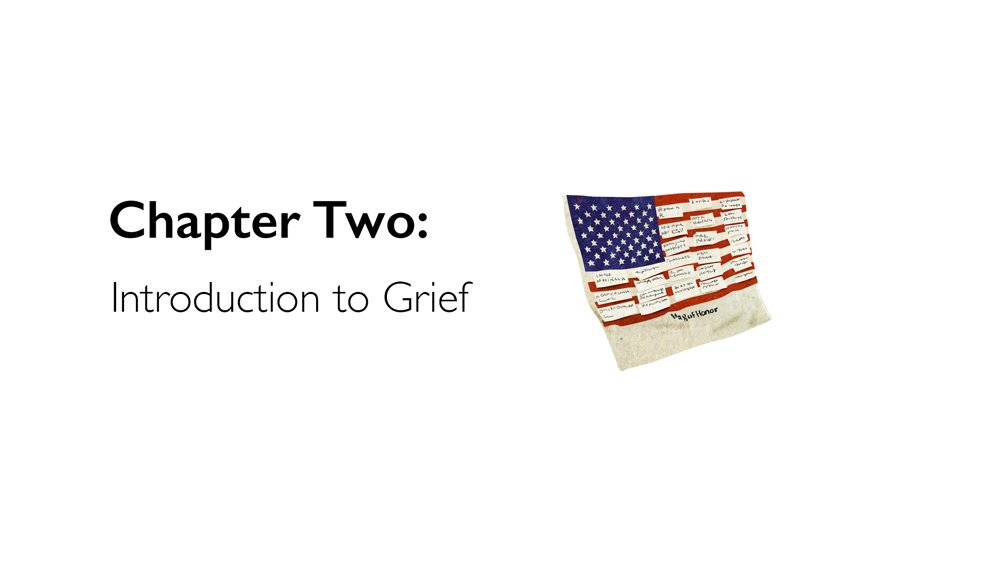

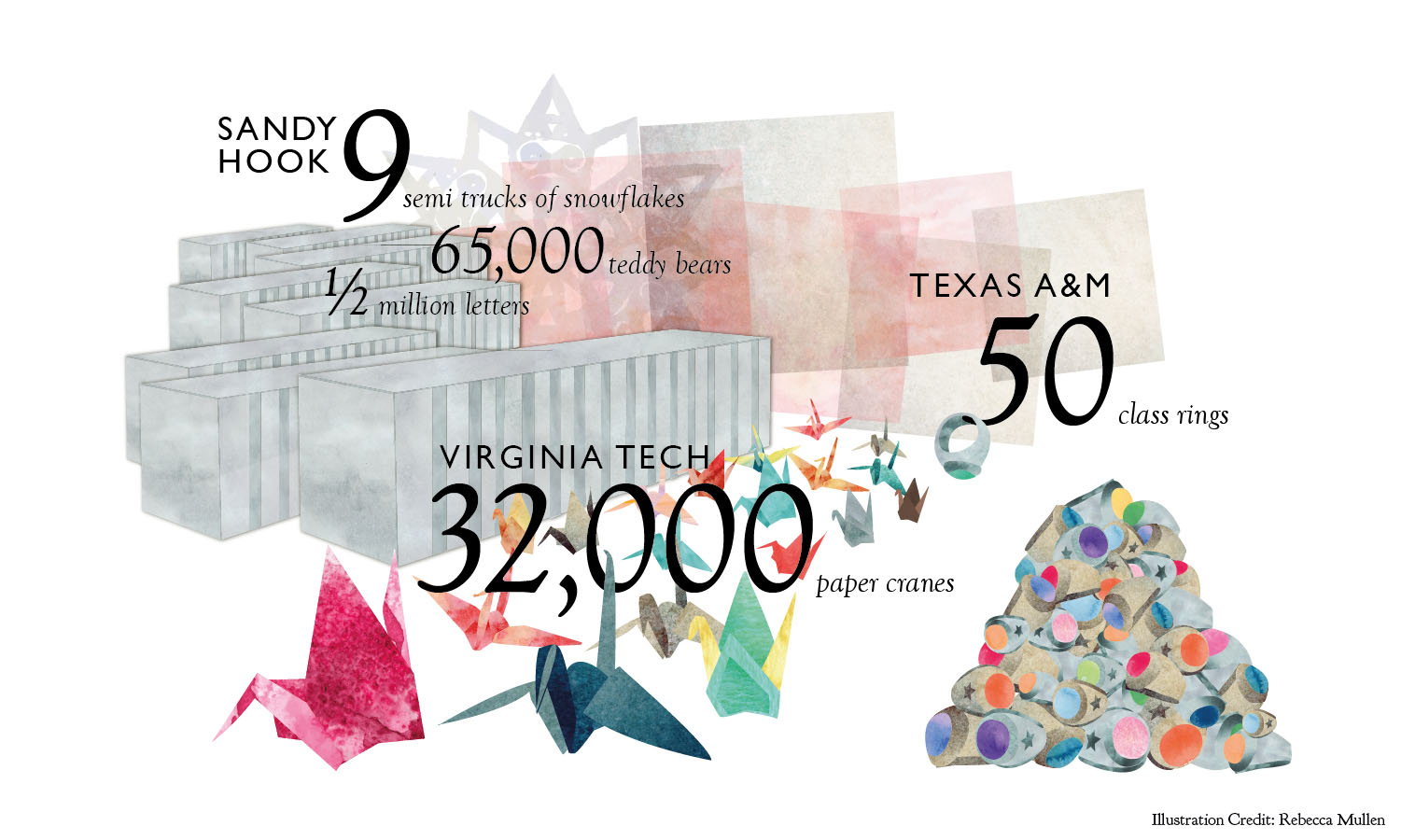

As people like Chris, Yolie, Ross, and Andrea came to terms with what had happened in their town on December 14, 2012, people all over the globe reacted to the news in their own way: They sent sympathy in the form of plush animals and Hallmark cards, grief bottled up in boxes of school supplies and Christmas presents. In just a matter of days after the Sandy Hook shootings, Newtown was inundated with donations and gifts.

The incoming packages would amount to more than 500,000 cards and letters, 9 semi-trucks of paper snowflakes, and 65,000 teddy bears—not to mention thousands of other donations or the half-mile long stretch of trees, votives, toys, and other condolences that lined the “Hook”—the strip of road that led from the local diners down to the Sandy Hook school entrance.

The typical emergency plans for small towns like Newtown don’t cover floods of teddy bears and donations, so with no official protocol or precedent for the amount of material coming in, it fell to individual citizens to respond and figure out what to do with all the stuff.

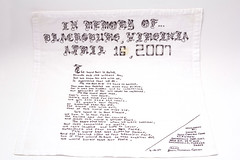

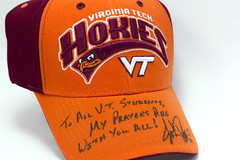

I hadn’t set out to make a documentary about Newtown. Instead, nearly five years after my experience of the Virginia Tech shooting, in the winter of 2012 I had just reached a place where I felt like I could look at the condolences people had sent to my community following our tragedy. I wanted to come to a better understanding of this incomprehensible thing I had both lived through first-hand and watched, in a kind of shock and disgust, on television. So, I visited the April 16th 2007 Condolence Archives, the permanent collection of stuff the university chose to keep in remembrance of that day and those lost.

As I began this exploration, news networks lit up with images of Newtown and, shortly thereafter, stories of the massive amounts of stuff sent to Sandy Hook could be found all across news websites, Facebook, and Twitter. By rough estimate, Newtown received at least ten times the amount of stuff that Virginia Tech did. I couldn’t help but wonder how Newtown would choose to deal with it—whether their choices would be different, whether their story would help me understand what people hoped to do by sending such things.

But, remembering the invasion of news crews at Virginia Tech—their zoom lenses hoping to document our grief—I kept my distance. I reached out to those dealing with the stuff via email and, after a hundred days had passed, I visited Newtown.

When I arrived, my gracious hosts showed me how they had each taken on some of the burden of the stuff. Over the next year, I tracked how the stuff wove in and out of their daily lives.

The first of Newtown’s citizens to meet with me was Chris Kelsey who spoke frankly as he described what those first few weeks were like. He showed me the vast warehouse he had been managing since December where volunteers sorted and re-distributed the stuff sent to Newtown. As we walked, Chris told me how he first met families of the victims just before Christmas day.

In emails and phone calls, Chris went on to recall how the post office was so overwhelmed that the quantity of mail shut down the regional sort facility. Mail sorters from neighboring towns donated their time—the first time in history, I was told, that they had volunteered—to help sort Newtown’s incoming mail. The 20,000 square foot facility he secured was needed for just over three months to manage the packages coming by the truckful each day from UPS, FedEx, and DHL. The list of “other” donations—such as trees to be planted in the victims’ honor, or memorial donations to other charities—soon stretched to over 600 pages.

As I made clear with anyone who asked in Newtown, it was impossible for me to approach this project with a news reporter’s clinical remove. For me, the story of Newtown’s stuff was intensely personal.

Caption

It smelled like popcorn on April 16, 2007. I had just begun projecting a movie at the Lyric Theatre in sleepy downtown Blacksburg, Virginia. It was an early morning show geared towards moms with small children and special needs patrons. I can no longer remember the title of the film. Just the smell of popcorn and getting a phone call. “There’s been a shooting on campus. Lock the doors.”

Everyone knows what happened next. In the weeks that followed, all the world over learned of the shooting that left 32 students and faculty at Virginia Tech dead, plus the shooter himself. The satellite trucks came and didn’t stop coming until the university’s enormous conference center parking lot was full. Our private grief became public.

Like so many people in Blacksburg—a town of only 40,000—I knew a few of the victims. The footage you see above is my sole document of those days. I used my Super-8 camera to film the town’s movie theater marquee, the stone memorials for the victims. Something about the silent film made it more permanent and also less real. And it certainly looked different from the footage I saw on television: this wasn’t an outsider’s “pornography of the real.”

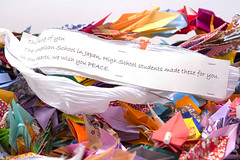

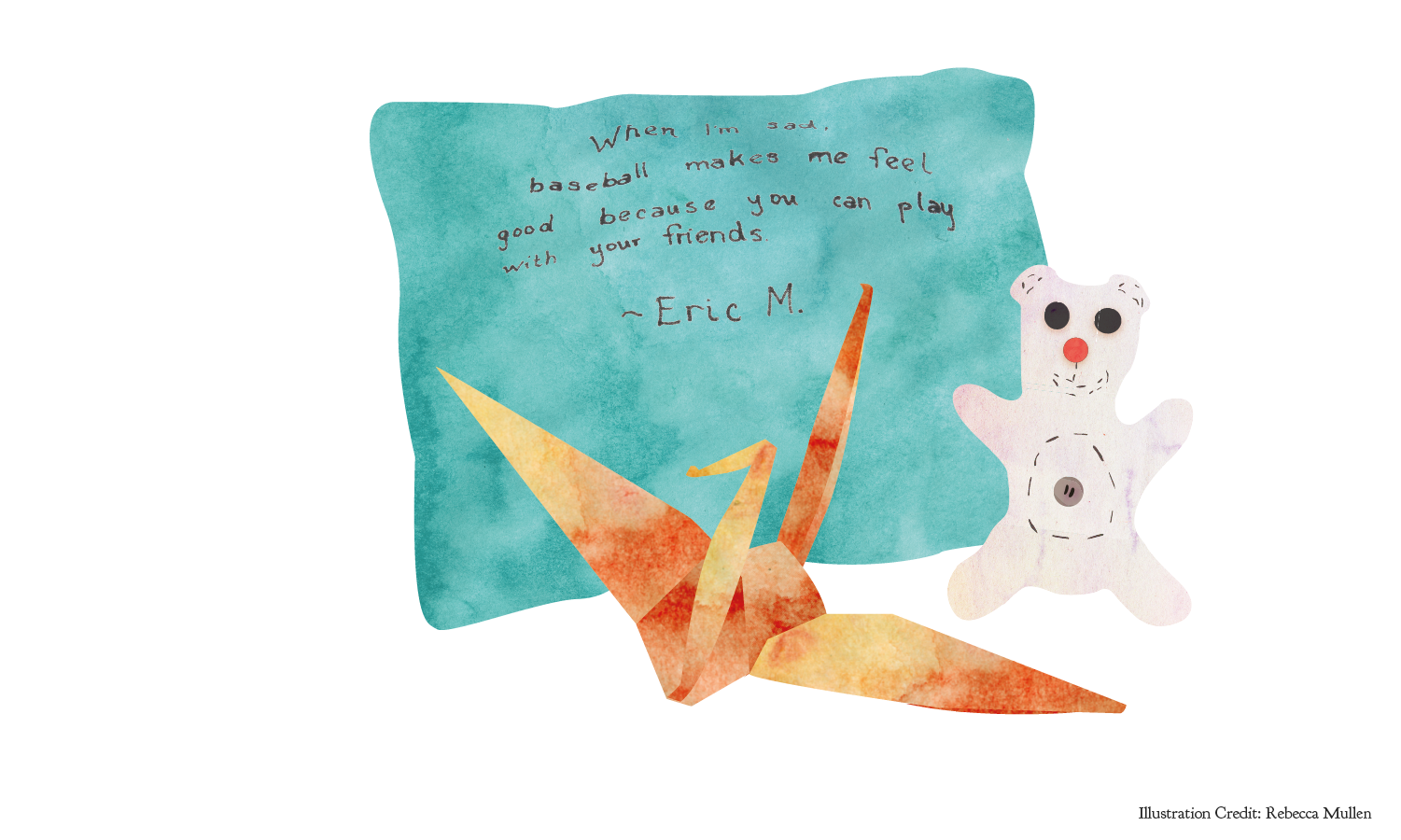

This was my home movie, and, as a filmmaker, the way I grieved—with my camera. The world, on the other hand, sent their sympathies in the form of stuff: Hundreds of banners and posters. Tens of thousands of cards and letters. 32,000 paper cranes. The packages kept coming.

Years later, as I watched the cycle repeat in Newtown, I began to ask myself why people do this and how long it’s been going on.

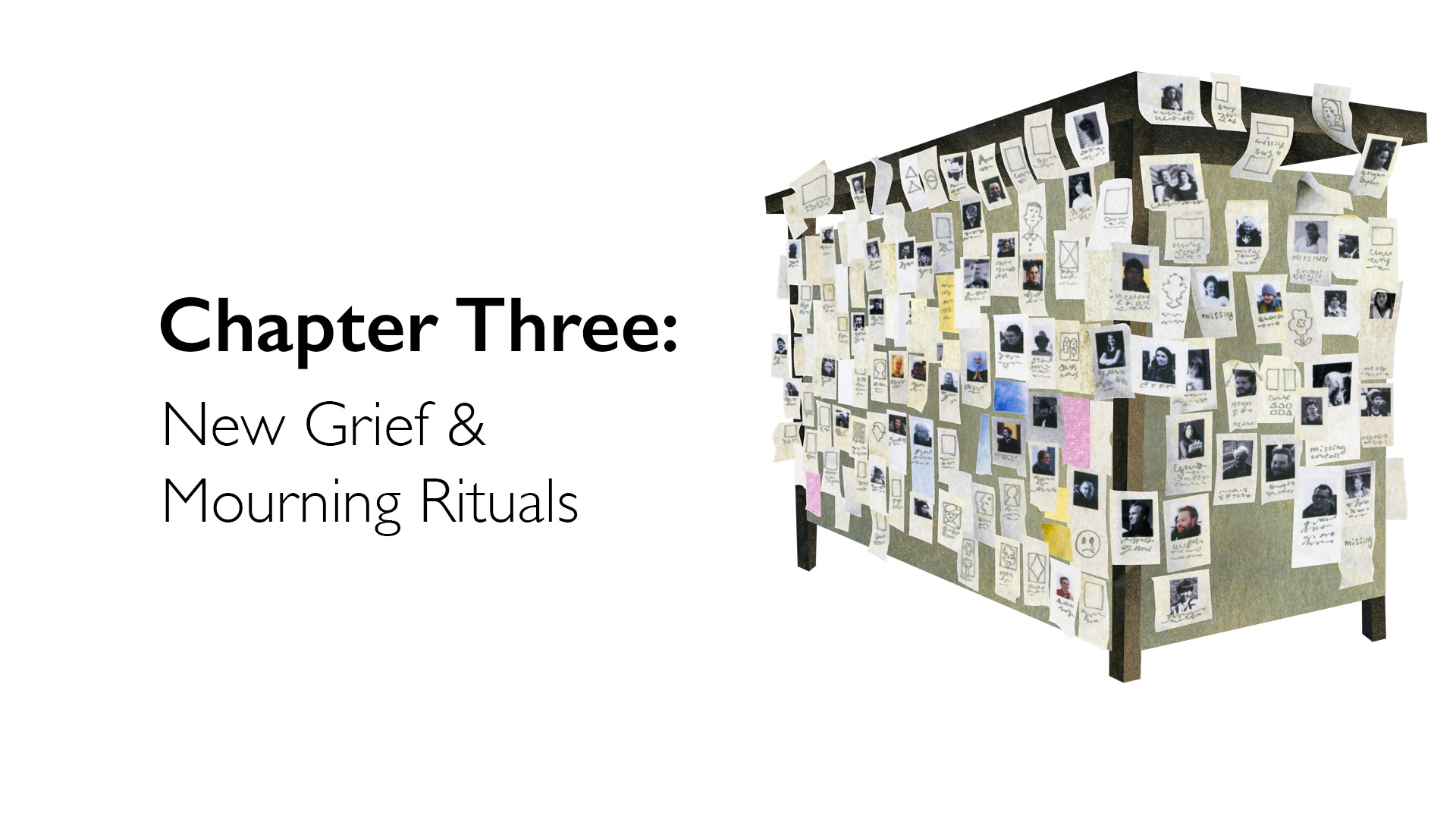

It’s hard for me to remember what real-life tragedies looked like before the Internet existed. Since at least 9/11 I can only remember mass tragedies accompanied by spontaneous shrines—a mass of handwritten notes and letters, votive candles, teddy bears as seen through instant images on the web and TV.

In my life, I only expected to see items like that on screen—never up close. Today, though, when I see news images or video of memorials of the latest tragedy, it reminds me of those days in Blacksburg. The candlelit vigils and piles of flowers—they are all different and yet somehow the same.

Struggling to understand these memorials and what they represent, I picked up Memorial Mania, Dr. Erika Doss’s book on America’s obsession with memorialization.

After reading Dr. Doss’s study, I traveled to Notre Dame, where Doss is a professor of American Studies, to ask her more about the history of makeshift shrines.

In our conversation, she explained how temporary memorials might be millennia old but how what happens today differs significantly from the past.

My experience at Virginia Tech was first-hand but in our conversation we discussed many others: Columbine. Texas A&M. Oklahoma City. 9/11. And, of course, the list has continued to grow in the years since: Aurora, Sandy Hook, the Boston Marathon.

Beyond these mass tragedies, there is a staggering number of school shootings too extensive to list. And every urban street corner has the potential to become a spontaneous shrine in a culture that has a national legacy of violence.

The speed at which we learn about tragedies hundreds and even thousands of miles away and the size of the shrines we build for the dead, the accumulations of our grief, seem inseparable.

A TIMELINE OF STUFF: Key Moments in the History of Temporary Memorials

I couldn’t shake how these “spontaneous shrines” or “temporary memorials” have evolved into something that is not to remain ephemeral, but something to be saved, kept, archived.

If we are, as Dr. Doss contends, “a nation of hoarders”, then I decided I wanted talk to some of the people charged with the task of preserving the stuff.

Caption

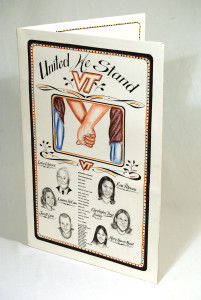

Tamara Kennelly is a bookish librarian, whose life’s work lives in the green-glow of a cavernous, fluorescent-lit archive. When I was a professor at Virginia Tech (from 2008-2012) we had met and talked about Virginia Tech’s April 16th archive.

But, ironically, it was only after leaving my position at Tech and moving away from Blacksburg that I returned to document Tamara’s work. But maybe it was the leaving, the remove, that made it possible.

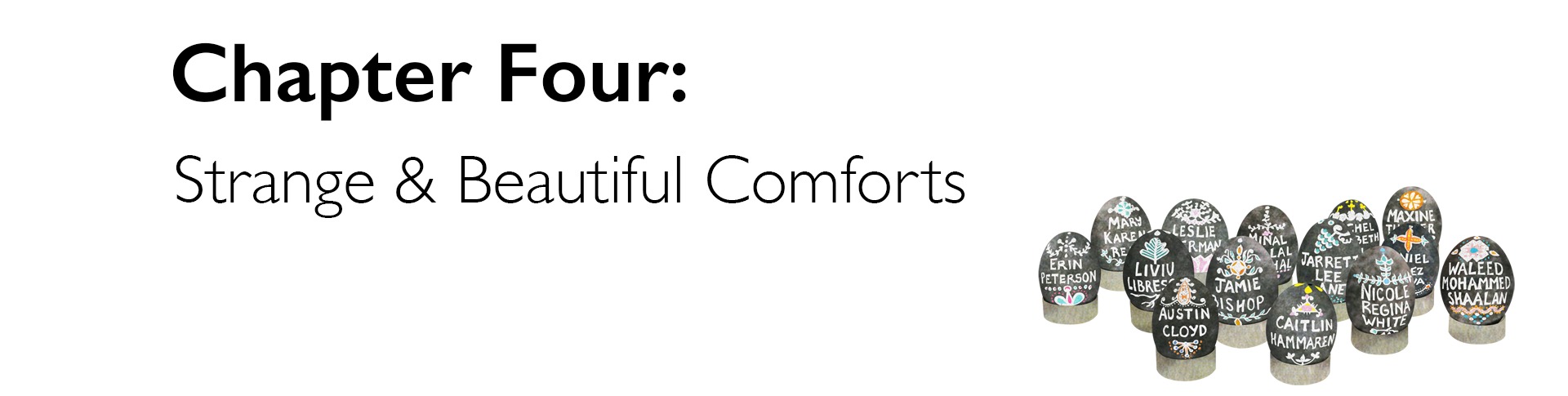

As I handled everything from hand-painted pisanki eggs to artwork from the incarcerated, Tamara explained to me the massive influx of items that were shipped to Blacksburg from around the world in the wake of the Virginia Tech shootings and how, as the University Archivist, it was her job to process it all.

As I explored the objects sent to the university in the wake our tragedy, I recalled something I heard on the radio one day: “Objects have lives. They witness things.” I don’t remember who said this, or in what context, but I began to believe these words.

Among the more predictable sympathy cards, banners, and paper cranes were all kinds of mysterious, strange, and beautiful comforts: a package with a box of Cheerios and socks, a NASCAR racing car hood, an American flag from NASA that orbited the moon, a baby doll in hand-crocheted Army fatigues. I was struck by the eccentricity and artistry of these items sent to comfort us in our time of grief.

Cataloging every one of these objects, each a painful reminder of loved ones lost, I came to understand Tamara’s quiet heroism through the five years of work that created the archive.

Tamara, however, wasn’t alone in doing this work. In particular, she received guidance from someone who had trailblazed how to archive these spontaneous outpourings nearly a decade earlier: Dr. Sylvia Grider, professor of Anthropology at Texas A&M.

I visited Sylvia in College Station where a 59-foot bonfire collapsed on Texas A&M’s campus—a tragedy that took the life of 12 students and injured 27 others—in the fall of 1999. I wanted to learn how the campus set out to document the outpouring of support that followed.

While much thought and consideration went into the archives at Virginia Tech and Texas A&M, there was not much debate about what to do with the materials—someone stepped up with an idea and a university structure was there to support it.

Newtown, however, was another story.

Caption

When the news networks lit up with coverage of the Sandy Hook School shooting, the small town of Newtown, Connecticut was not prepared for the media invasion or influx of stuff that was to follow.

A town of just 27,000 residents, Newtown lacked sufficient existing infrastructure to cope with the unprecedented amount of condolence materials it received. To put it simply, Newtown received at least ten times the stuff of Virginia Tech with less than a quarter of the resources.

And there were very different opinions in town about what should done with the stuff.

With no official plan or even a historical precedent for the amount of material coming in, it fell to individual citizens to respond to the outpouring of stuff. Several stepped up to the task, albeit with different approaches. After a hundred days had passed, I visited the town and caught up with the different efforts to manage the donations.

Chris and Ross were among the first to respond to the stuff coming in—Chris, because of his position as assessor in the town, and Ross, because he had visited the town hall in the immediate aftermath to see the bins of mail left out for townsfolk to read. Each voiced very different opinions about what, ultimately, should be done with the materials coming in.

Ross’s support for saving the tens of thousands of letters to Newtown was clear. Chris, on the other hand, expressed mixed feelings. Living through the letters, which remained on display for six weeks at the town hall outside his office, was “like living at a wake.” Perhaps it would be better for the town to get rid of all the reminders? Who would want to see these things in 20, 50 years? These were some of the questions he considered.

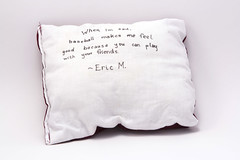

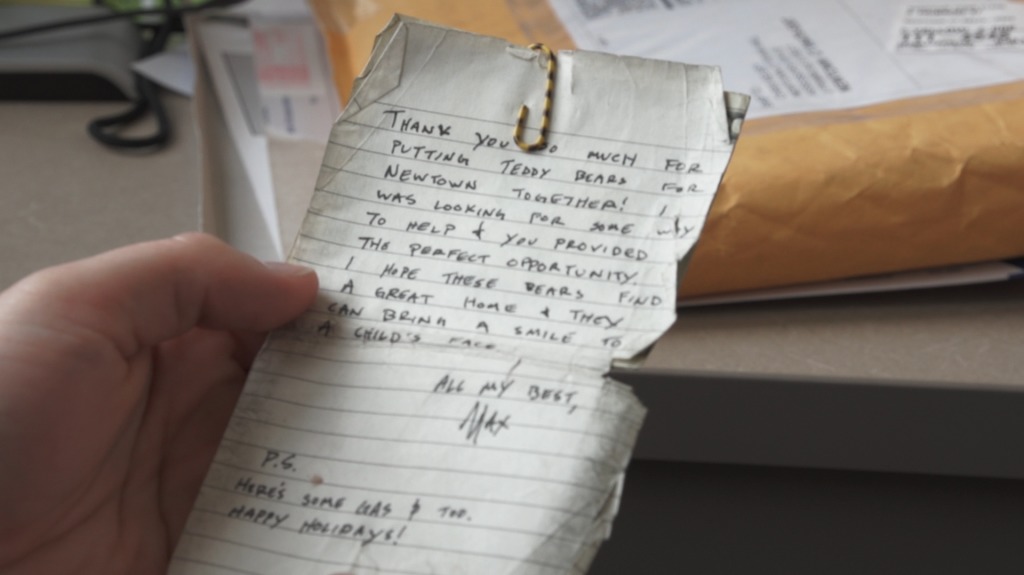

Nonetheless, Chris couldn’t shake a personal connection to a memento of his own. During our interview, he showed me a hand-written note he kept tucked away in his wallet that came attached to one of the 65,000 teddy bears that came into town before Christmas:

Chris said he imagined the kid who sent it, Max, had about $4 to his name and wanted to send that in as well.

***

Despite the relatively small size of the town of Newtown, communication among different response groups was not coordinated—it was too much for any one entity or even the local government to manage—and it was challenging to keep track of all the different efforts happening around town. To get an idea of just how many activities were happening, the Newtown Volunteer Task Force set up a 1-800 hotline to help manage all the phone calls and inquiries coming into town. And at the donations peak, New Year’s Day of 2013, the work at Chris’s warehouse required over 100 volunteers.

Without a centralized coordinator, rumors about what to do with all the stuff swirled around town: Would letters be burned? Would donations be discarded? What, if anything, would be kept?

By early March 2012, two independent efforts to begin preserving some of the materials coming in were already under way, though the details about how much would be saved and how it would be preserved were still murky. Yolie Moreno, a local artist and activist, had set out to photograph each and every one of the more than 500,000 letters sent to Newtown in an effort to “share the love”; meanwhile, the town’s library had begun initial collecting and planning for a small archive of items sent to the town.

While the eventual plans for the “Embracing Newtown” letter documentation project and library archive were still uncertain, what was clear to me was the care and reverence with which Yolie and Andrea took on their work. The stuff of our grief—the cards and teddy bears, the letters and quilts— seemed to take on what Dr. Sylvia Grider in Texas had described to me as a “luminous aura.” No matter how mundane, the stuff became sacred by the very fact that it had been sent here, at this time and place, to provide comfort.

Caption

Six months later, and a total of nine months after the shooting, the donations had slowed but the struggle over what to do with all of Newtown’s stuff—sacred or otherwise—was still going on.

It was now September, just three months from the one-year anniversary of the shootings, and everyone had begun adapting to the “new normal.”

After initial preservation efforts that led him to reach out to Mother Jones and The New York Times, Ross discontinued his “Letters to Newtown” Tumblr site and let others pick up the torch of preservation efforts.

When I caught up with Chris, he described returning to a life with just one full-time job. He also alluded to the rumor that had circled around town—that some of Newtown’s stuff, the things that couldn’t be re-gifted, weren’t suitable for an archive, or not appropriate, would be burned and turned into “sacred soil”—an ash that could be put into a permanent memorial. He said simply, “I think it’s time for that stuff to go.”

Andrea and Yolie, however, still found their lives entangled with the fate of the stuff.

Yolie had become the de facto caretaker of a giant bulk of stuff. Her charge included sorting the 500,000+ letters and artwork sent to town and any items not re-gifted or re-directed before Chris and his group shut down the donations warehouse.

Over the summer, the donated “Newtown Healing Arts Center” space where I originally met Yolie was bought by a wine shop, and she had to move all of her letter documentation project equipment out.

A POD full of unscanned letters and artwork was moved next to the barn on her property, where she continued her efforts, sometimes with volunteers, but most often on her own.

Andrea worked a little bit each week using her library training to make selections for two modest preservation efforts: a collection of about 1000 letters to be scanned and hosted online by the Connecticut State archives and another small permanent archive of three-dimensional objects to be stored off-site in donated storage from Iron Mountain, a national records storage and management company.

***

When I asked Yolie what would happen to all of the stuff once she was done with her scanning, she didn’t know. The rumors of “sacred soil”—that is, burning items being stored at the town’s highway garage into an ash that could be later incorporated into bricks for a permanent memorial—that Chris had told me about appeared to be a real possibility. And Yolie seemed to be slowly coming to terms with the unfeasibility of her wish to document each and every letter that came to town.

Yet, despite this realization, each time she went to the warehouse to drop off items for the discard pile she was visibly torn between a desire to let go and move on with her life and an uncontrollable urge to save what she considered precious.

Watching Yolie and seeing the enormity of the warehouse, knowing its items would likely be burned—transformed into “Sacred Soil”—I couldn’t shake the question, Why? Why do we send these items? What is our responsibility to them if they are ours?

Some things would still be selected and collected by the library; others, Yolie said, she would hang on to in hopes of creating a future art installation. But as for the bulk of it, the town still wasn’t sure. The weather-trodden memorial items would have to go—they were taking up too much space in the highway garage that would soon be needed for snow equipment once winter hit. There were also items the families didn’t want themselves and didn’t want re-directed—because they were personalized with images of the deceased, too painful, or distasteful for public display.

By late fall, the notion of a big burn seemed imminent and Yolie put me and my crew on standby. The plans wouldn’t be announced or publicized and could happen at any time. And, sure enough, one day in October I got the call: workers were loading the stuff into transport trucks and the burn was going to happen at about four a.m. the next morning.

Caption

Leading up to Newtown’s one-year anniversary, there were fears about another massive influx of “stuff.” The town’s first selectman made public statement after public statement asking folks not to send any more stuff and for the press to keep their cameras away to leave the town alone—to let them grieve in peace.

I returned to Newtown for the anniversary but confined my camera to the private homes of Yolie and Chris, to see if they could fill me in on the final chapter of the story of the stuff.

Where did it all go?

How much was documented?

What remained?

Chris also caught me up on all the big changes in his life while Yolie expressed relief that her photography project, titled Embracing Newtown, was now complete. The majority of letters were kept, put into archival housing and stored at the Connecticut State Library. Artwork from around the country was either burned into “sacred soil” or selected for preservation by Yolie for a future art installation.

Being invited into the homes of Chris and Yolie on such a significant anniversary reminded me of a conversation with Ross earlier in the year during one of my return visits. After the camera stopped rolling, we continued to talk about how life changes after a public tragedy, how it makes you wary of cameras and what they set out to capture, how images can and will be used for different ends. Ross then looked at me and said, “But you’re one of us.”

Caption

Nothing, probably, will ever answer what drives us to memorialize. It can’t be put into words. At Texas A&M, Dr. Sylvia Grider told me the most common answer she received to this question was, “I had to. It was the right thing to do.” Yet I realized that, throughout the process of documenting, I hadn’t spoken with a single person who had been responsible for sending a letter or item to Virginia Tech or Sandy Hook or anyplace.

Could asking one person to explain their motivations speak for everyone? Would this person’s explanation stand in for us all? Of course not. But I wanted to ask.

Something that fascinated me about the public response at Virginia Tech was how many letters and packages we had received from the incarcerated. To be sure, I imagined that population might have a lot of time on their hands….but why would an inmate want to express sympathy to us? In particular, we received letters and gifts from those who, at least in the eyes of the court, were serving time for violent crimes they had committed themselves.

As I thought about this paradox and sorted through various items and tried to track down the senders, I reflected on what it must mean to know suffering from both sides. Is that sympathy of a different kind than my own?

One of these items I found among Virginia Tech’s collection was a hand-drawn card with two clasped hands from a prisoner in Kentucky.

After searching for the inmate, I found he had been transferred to a medium security penitentiary in Pennsylvania. After multiple denied requests for permission from the prison administration to film an interview, I spoke with the card’s sender, Jaime Davidson, inmate #37593-053, by phone. The recording that follows is our conversation.

Jaime spoke of the bureaucratic challenges he encounters trying to do good for others; he talked of a deep and burning desire to build a meaningful legacy for himself. While I couldn’t begin to assess his guilt or innocence (for more on that story, listen to a full interview here), Jaime was able to sum up and answer the “why” so simply, with an explanation that had eluded even the esteemed scholars: “Everybody finds a way to do their sentence.”

What he said to me didn’t strike me so much as the words of someone incarcerated as much as those of someone who, like all of us, is prisoner to the human condition. For Jaime, for me, for all of us swept up in grief, we don’t choose our sentence—the time we serve suffering—only the way we get through.

Send Support Not Stuff!

After seeing how overwhelmed communities can become by the outpouring of mail and donations, we wondered if there was a way to reverse the flow of stuff to people in positions to effect meaningful change to prevent gun violence.

We've created a blank PDF template to help you mail peace cranes to legislators and changemakers following mass shootings. Add your own message about concrete actions you'd like them to take, such as mental health care solutions, blocking gun sales to domestic violence offenders, and background checks for all gun sales.

Rather than contributing to the overload of stuff, you'll send a powerful message to lawmakers, which counts more than emails or phone calls. We also welcome you to support this ongoing work with a tax-deductible donation!

Additional Educational Materials:

— Case Studies & Best Practices for Crisis Managers - Now Available!

This chapter aims to provide insight and guidance to librarians, archivists, or crisis managers who must develop their own unique response to unanticipated and unthinkable tragedies. Response strategies are covered in both a discussion of the history and literature surrounding temporary memorials and three disaster case studies: the 1999 Texas A&M Bonfire Tragedy, the 2007 Virginia Tech Campus Shooting, and the 2012 Sandy Hook School Tragedy.

— A Module for Students of Library & Information Science - Now Available!

This module is an online, interactive lesson designed for graduate students in Library and Information Sciences. It includes images, video, and exercises to explore the role of libraries and archives in documenting and preserving the materials left at temporary or makeshift memorials. It may used in conjunction with exploration of the web documentary or as a standalone tutorial.

Project Credits

A Web Documentary by Ashley Maynor

Illustrations: Natsko Seki

Executive Producer: Paul Harrill

Cinematographers: Paul Harrill, Abbey Hoekzema, Sunrise Tippeconnie, Dan Caudill, Joan Stein Schimke, Alex Stergiou

Original Music: Jason Staczek

Animator: Kent McQuilkin

Additional Illustrations: Rebecca Mullen

Additional Music: Phil Symonds, Zero Bedroom Apartment

Sound Mixer: Pete Carty

Funded in part by the University of Tennessee Knoxville Libraries

Published April 16, 2015